Food for thought on Gaza’s runaway inflation from Frances Coppola.

Inflation, we are told, is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”: too much money chasing too few goods. Allowing the money supply to grow faster than the productive capacity of the economy causes inflation.

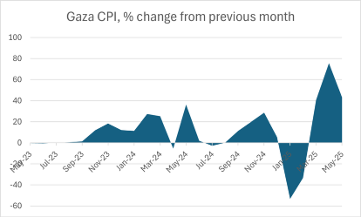

Hyperinflation is extremely rapid inflation. The Cagan definition of hyperinflation is a monthly inflation rate of 50% or more, but hyperinflation is a trend rather than a level: very rapidly rising inflation is hyperinflation whether or not it has reached that figure.

We are told that hyperinflation is caused by central banks printing money to support the spending of a profligate government and enable it to pay its debts. Advocates of gold standards and Bitcoin insist that hyperinflation is a problem exclusive to fiat money systems. They point to the fact that major hyperinflations such as Weimar and Zimbabwe happened under fiat currency systems. If central banks couldn’t print money, there would never be hyperinflation.

Since March 2025, Gaza has been in hyperinflation. The monthly inflation rate rose from minus 33.29% in February to 75.59% in April. It has dropped back slightly since then, to 43.21%, but it’s still broadly in hyperinflation territory. This chart shows an extraordinary swing from rapid deflation in January 2025 to rapid inflation in March:

(figures from the Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics)

Now here’s the mystery. Gaza doesn’t have its own currency: it uses the Israeli shekel. There’s no central bank to print money, and no government issuing debt to support profligate spending. The money supply in Gaza has been fixed since October 2023, when Israel froze the supply of cash shekels and imposed liquidity restrictions on Gaza’s banks. Severe liquidity shortages and damage to branches and ATMs forced banks to close– the last one closed its doors in August 2024. Some reopened during the January to March 2025 ceasefire but have now closed again. There’s no bank lending.

And yet there is hyperinflation. Why?

At first glance, there’s an obvious culprit. Anyone who uses social media will have noticed continual demands for donations from cash-strapped Gazans. Despite attempts by some of the major fundraising platforms to shut them down, there are hundreds of fundraising appeals of the “save my family from starvation” variety. Currencies accepted include dollars, euros, dollar-pegged stablecoins and Bitcoin. And the amounts raised can be substantial: some fundraisers reach targets of $20,000 or more.

Could donations be causing Gaza’s hyperinflation? Is there, in fact, a problem of too much money chasing too few goods?

Nearly all transactions in Gaza are in physical cash. Use of digital money increased during the January to March 2025 ceasefire but has fallen since due to internet outages and restricted electricity supply. But the supply of physical cash is falling as banknotes degrade, though there’s a small industry refurbishing them to keep as many as possible in circulation. There is a severe shortage of physical cash in Gaza.

Since nearly all transactions are in physical cash, e-money, whether bank deposits, digital wallets or cryptocurrency, must be exchanged for physical cash before it can be used. Money changers are charging commissions of as much as 45% of the exchanged amount for good quality banknotes. The effective exchange rate between e-money and cash is no longer 1:1. It is rapidly approaching 2:1. A shekel of physical cash is now worth nearly twice as much as an e-money shekel.

While the Gazan economy continues to run on physical shekels, e-money – whether shekels, dollars, euros, stablecoins, Paypal credits or Bitcoin – will continue to be worth less than physical cash. Indeed, because the quantity of physical cash is fixed (and gradually falling through attrition), the more e-money enters Gaza, the more its value will fall relative to physical cash. Donations are driving down the effective exchange rate of all forms of e-money.

We last saw an effective exchange rate crash like this in Greece in 2015, when the ECB restricted the quantity of physical cash entering the country and the Greek government closed the banks to prevent bank runs. And as in Gaza, it caused a kind of hyperinflation. The value not only of physical cash, but of durable goods that could be bought with e-money and sold for physical cash, rapidly rose.

Thus, the collapsing value of e-money (dollars, euros, dollar-pegged stablecoins, even Bitcoin) relative to physical shekels contributes to the hyperinflation that has taken hold in Gaza since Israel imposed a total blockade in March.

But it’s far from the whole story.

Gaza is under siege. Hyperinflation in a siege economy is primarily caused by rapid catastrophic collapse of the supply side. It is the inevitable effect of the sudden cessation of essential imports in a monetised economy whose productive capacity has been destroyed by war. To call it a “monetary phenomenon” is nonsensical.

When hyperinflation happens in a country with its own currency, the usual means of ending it is to peg to a hard currency or gold, or to adopt a hard currency as the main medium of exchange. But that’s not possible in this case. Gaza doesn’t have its own currency.

Widespread adoption of e-money as medium of exchange would bypass Israel’s squeeze on physical cash and stabilise the e-money exchange rate. But electricity supply and internet connection are highly unstable in Gaza. There are frequent outages due to Israeli bombing and a lack of parts for repair/replacement of damaged infrastructure. And in many places, there’s no internet connection at all. So Gazans are unable to rely on digital transactions.

Counterfeiting would relieve the pressure on the supply of physical cash, reducing the incentive for money changers to charge exorbitant commissions. However, Israel blocks the import of paper and printing inks.

Cash-strapped people are also resorting to informal barter. Barter systems often develop when money becomes either impossibly scarce (Gaza) or worthless (Weimar).

But none of these measures can resolve the main problem – the disastrous shortage of goods that is sending prices sky-high.

In a situation like this, what is really needed is a demonetised rationing system. That’s what the NGOs that formerly provided humanitarian aid operated. And that’s where the extraordinary deflation of January-February 2025 comes in.

During the ceasefire, Israel allowed humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip in the largest quantities since before the war. It was distributed by NGOs and private sector actors. As a result, the prices of goods sold through commercial outlets rapidly fell. Additionally, the Hamas-run government capped commissions charged by money changers at 5%. Digital transactions rapidly increased as money changers shut down operations that were no longer profitable and electricity and internet connections became more stable.

But these welcome developments reversed abruptly when Israel imposed its blockade.

The GHF aid system, inefficient and brutal though it is, may be calming price rises a little – the rate of inflation in May dropped below the Cagan threshold. But it also appears to encourage commercial resale of aid. So it may be that the rate of inflation has fallen simply because exhausted people are no longer buying food.

Gaza’s hyperinflation, like the deflation that preceded it, is fundamentally a supply-side problem, not a monetary phenomenon. In the absence of an effective humanitarian rationing system, further restricting the amount of money in circulation would be a recipe for famine.

The solution to Gaza’s hyperinflation is not less money, it is more goods. Lift the blockade, implement an effective humanitarian rationing system, and demonetise the economy. And above all, end the war. The only long-term solution to the economic destruction brought by war is peace.